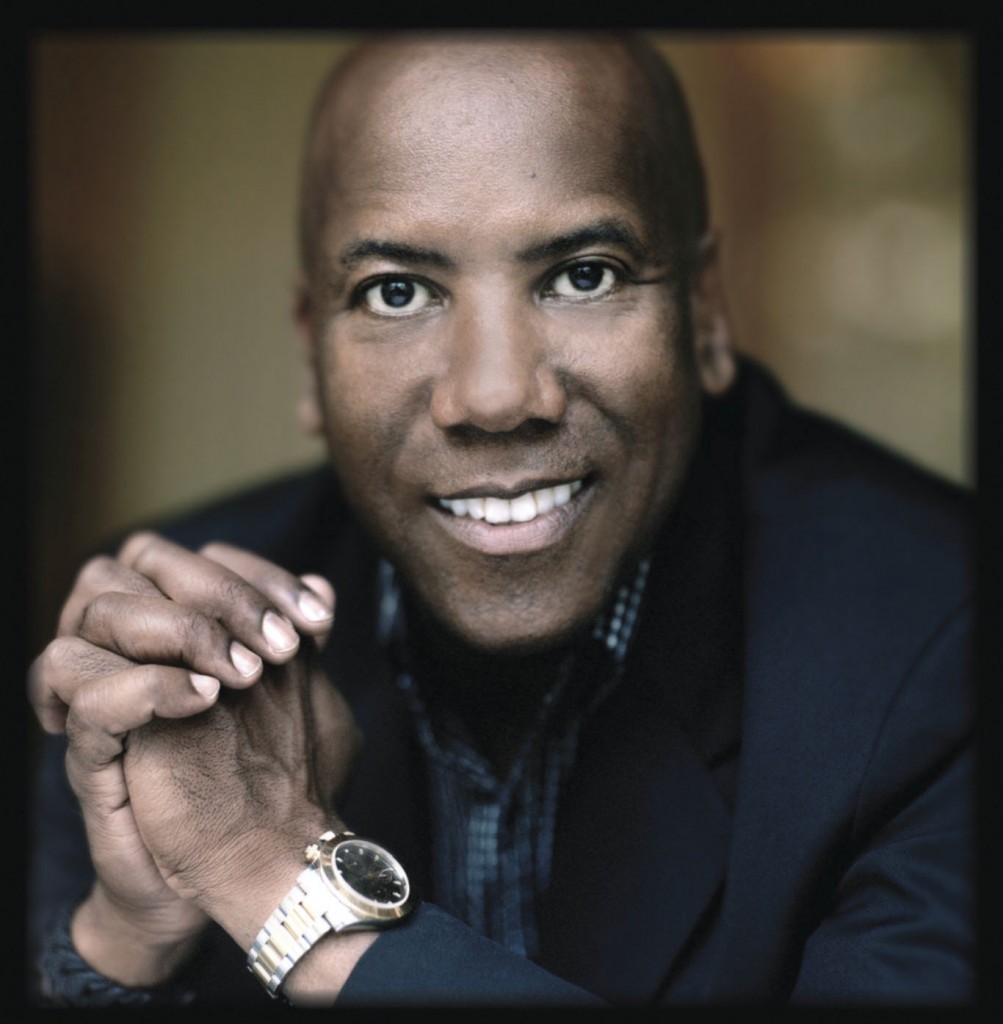

Bass Great Nathan East on Music & Fourplay

by Veritas on Oct.31, 2012, under Press &Reviews

The former San Diegan is one of the most in-demand bassists of the past 30 years.

Get out of town!

It was while earning his degree in music at UC San Diego in the late 1970s that budding bass guitar great Nathan East received perhaps the best advice anyone has given him.

“My two mentors were Bert Turetzky, who I rigorously studied upright bass with, and Cecil Lytle, who really took me under his wing,” East, also a Crawford High School graduate, recalled. “They were two of the best teachers I ever had. Bert’s big advice for me was to move to Los Angeles and to jump in with both feet.”

Given how fruitful his subsequent career has been, it might appear to casual observers that East jumped in with far more than just two feet.

After heading to Los Angeles in 1979, he quickly became one of the most prolific, diverse and in-demand bassists anywhere.

It’s a status he has maintained ever since, whether touring the world with Eric Clapton for nearly 20 years, accompanying a slew of legends at President Obama’s inauguration concert or serving as the musical director for music legend Quincy Jones’ recent all-star career retrospective concert at the Hollywood Bowl.

“To this day, I’m way busier than I ever thought would be possible,” said East, whose recent credits include recording sessions with Stevie Wonder, Michael Bublé and Daft Punk.

“In the busiest of times, I can remember doing as many as 28 (recording) sessions in a week. Even when I (only) averaged three sessions a day, that still came out to more than 700 a year.”

But it is the quality of his performances, not their quantity, that has helped East stand out for more than 30 years.

“Musically, Nathan is in (my) Top 3 as a bassist,” Clapton said in a 2005 U-T San Diego interview. “He’s the most supportive and caring musician I’ve met.”

He is also an accomplished vocalist. During East’s long tenure in Clapton’s band, he would perform lead vocals on the Blind Faith classic “Can’t Find My Way Home” (a role originally handled by Steve Winwood).

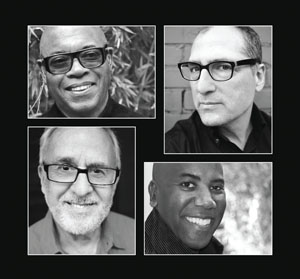

East performs two shows in San Diego with the pop-jazz band Fourplay on Friday, Nov. 2, at downtown’s all-ages Anthology. He co-founded the chart-topping group in 1991 with keyboardist Bob James, drummer Harvey Mason and guitarist Lee Ritenour (whose role is now ably filled by Chuck Loeb).

The veteran bassist’s ability to play with skill, sensitivity and just the right touch are key reasons he has thrived for so long. The fact that he is widely regarded as a genuinely nice guy is another. Then there’s his impressive versatility, which has enabled him to shine whether playing with such jazz luminaries as Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter or with Rock and Roll Hall of Famers like George Harrison and Rod Stewart.

Yet, it’s likely that many pop music fans are familiar with East’s impeccable bass playing even if they don’t recognize his name. That’s because he has made indelible contributions to such ubiquitous songs as Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven,” Michael Jackson’s “Bad,” Kenny Loggins’ “Footloose” (which he performed with Loggins at the 1985 Live Aid concert) and the 1984 Phil Collins/Phillip Bailey hit, “Easy Lover” (which East co-wrote).

Then there are his memorable performances on albums by everyone from B.B. King, Bob Dylan and Barbra Streisand to Aretha Franklin, Beyoncé and rock guitar hero Joe Satriani.

“I diversified early on,” East, 56, said. “I didn’t ever want to be known for doing just one thing and, then — if it dried up — it would be over. It’s fun to keep your hand in the jazz world, the R&B world, the pop world, the rock world, and anything in between.

“Fourplay just got back from a week (long) ocean concert cruise, then we went to play in Aruba. The next day I was in a (Los Angeles) studio with Burt Bacharach, who is working on an album with (longtime Elton John lyricist) Bernie Taupin. In Aruba, I ran into Chaka Khan, who said she needs (new) songs, so I’ll try to write for her.

“I’m also producing the title track for the new Anita Baker album. You just do what you do and don’t look back. I feel very blessed, because it still keeps going.”

East’s formidable talents were already evident when he was barely a teenager.

It was then that he co-founded Power, a jazzy San Diego funk band that also featured such precocious talents as keyboardist Carl Evans, Jr., and saxophonist Hollis Gentry, III. By the time he was at UCSD, East was a member of The People Movers, one of San Diego’s top cover bands.

His bass playing was so accomplished that, just weeks before graduation, he was offered a position in the then-latest band led by fusion jazz guitar giant John McLaughlin.

“It was very difficult to turn down and everybody thought I was absolutely nuts not to play with McLaughlin,” East recalled.

“But my grandmother said: ‘If you don’t do but one thing for me, finish school.’ I ran into John this year at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, and he looked and sounded great. Every now and then, I wonder what my path would have been like if I’d accepted his offer 33 years ago.”

East, who lives in Los Angeles with his wife and two children, happily continues to play on numerous albums that cover the gamut of contemporary styles. But he laments some of the transformations that have reshaped the music business.

“The industry has changed a lot and so has the playing field,” he said. “There are not many CD stores left. A friend of mine was trying to find the latest Fourplay album and went to four places. He wound up finding it at a Barnes & Noble store. That’s the sad thing: In less than 30 years, we’ve lost the CD.”

The decline of the CD — and, with it, album sales — has had a tangible impact on Fourplay, whose self-titled 1991 debut topped Billboard magazine’s Contemporary Jazz Album charts for 33 weeks.

“Our first CD sold over 1 million copies and the next two both went gold, which is 500,000 copies each,” East said. “There’s no doubt that, for everybody, the numbers aren’t what they used to be.”

Concurrently, the smooth-jazz market that Fourplay once dominated has all but evaporated as a force on radio, with only a handful of stations in the country still maintaining the format. San Diego’s KiFM, a national smooth-jazz pioneer, last year shifted to a pop-vocal format. A growing number of smooth-jazz performers have in turn shifted to a more straight-ahead jazz style.

But there may be a silver lining. Smooth-jazz had become increasingly rigid and artistically stifling, even for a band whose members are accomplished as East and his colleagues. The format’s commercial decline has had a liberating effect on Fourplay, whose 12th album, “Esperit De Four,” was released last month.

“It definitely frees us up, when you no longer have that element of commerce hanging over your head. So, creatively, it’s a bonus,” East said.

“The first song on our new CD is more than seven minutes long, so there are no rules (now). We get to make music we absolutely love, and there’s no one saying: ‘Oh, you have to add sax to this song’; or ‘It can’t be longer than three minutes and forty seconds;’ or ‘No solos!’ We’ve taken off all those restrictions, so — artistically — it opened things right up.

“Why did the (smooth-jazz) format die? Because they didn’t want music anymore. The format got so narrow, it disappeared.”